There has been so much on social media recently about ableism. One tweet “abled bodied privilege is ….the advantage people have simply for not being disabled’ got me thinking. Sorry, I don’t recall who posted this. During the summer term, I was invited to give 2 mainstream school assemblies about ableism. These were well received by students and staff but prompted a lot of self-reflection. I’d kept the sessions broad brush, especially given the time constraints in schools. However, I was able to draw on my own lived experience of ableism and communication impairment. Ultimately my reflections have made me question if all disabled people are treated the same by the general population.

Not all disabilities are the same

As someone with multiple disabilities, I use a power chair, wear hearing aids and need a communication aid. Whilst around 20% of the population are classed as having a disability we are not all the same. Just like within the general population there are numerous sub-groups. One size does not fit all with the vast array of conditions covered. Even within disability sub-groups, people are not the same.

If we take deafness as an example. There are those people who sign or have a cochlear implant or wear hearing aids. Then there who lip-read or’ just’ struggle in some environments. Some people use multiple strategies, for instance, I have hearing aids and lip reading.

Wheelchair users are not all identical. There are those with manual chairs, some who are pushed and others who self-propel. Some people add a power pack for long days out. Additionally, there will be people with power chairs driving independently and some who will have assistant controls.

Just these 2 examples suggest it is hardly surprising the general population can sometimes feel unsure about disability.

My communication aid is just my voice

In the same way, not all communication impairments are the same. When it comes to communication there is a difference between receptive and expressive communication. Receptive skills refer to the ability to listen, receive and process information. Expressive skills are the ability to convey thoughts, emotions and feelings. Often it can be assumed a deficit in one area means an issue in the other, definitely, it doesn’t. In my case needing a communication device does not mean having either an expressive or receptive impairment.

With access to an electronic voice, I can express myself in a way others understand more easily. I have a physical speech challenge called dysarthria. This results from a weakness of muscles in the mouth, tongue and throat. As a result, it means my device is just a tool for getting my thoughts, feelings and emotions aired and shared.

We can be judged by the different tools and resources used

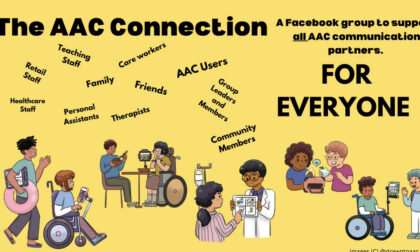

Then there are the types of communication tools and resources afforded to each individual. I’ve got a lifetime of close-up experience and observations. I see a difference in how these tools and resources change how people with communication impairments are viewed. Often those people who need support to communicate appear to be treated as less able than someone with an electronic system. So, needing a communication partner to interpret or facilitate an interaction sends a subconscious message.

I’ve also noticed that my different devices over time have meant I was treated differently too. I was 9 when I moved from having a symbol-based electronic communication aid to a text-based system. Immediately with the text-based system more people were interested and spoke to me age appropriately. I assume this was because they realised I had to be literate to type. Interestingly, my move to using an iPad in the last couple of years has been, with some groups, another game changer. A general familiarity with widely used technology can make some interactions less scary for others.

AAC users are just like everyone else

I’ve done it in the past, and at times I still do. I’ve called myself an AAC user. Without intending I have given myself a clear label, yet we are all so much more than this. I don’t use just a communication device. As a communicator, I am just like everyone else. These days I prefer the term multi-modal communicator as no one uses only one form of communication. For instance, I dip into everything to get my message across. Besides my communication device, I draw on verbalisations, facial expressions, eye movements, body language, gestures and environmental props. To my mind, this is exactly the same as someone who uses spoken language to communicate. Imagine you are explaining to someone how to juggle, it is likely you will automatically support your verbal message with actions and facial expressions.

Judging a book by its cover

Did you watch the Stephen Hawking film, ‘the theory of everything’? On film, it appears no one ever doubted his cognitive ability once he was disabled. In real life, maybe fame went before him. It appears that his name was enough for people to accept him without making judgements about his understanding.

So, what is it that strangers see when they see me and others with complex communication needs? Does the technology create a barrier? Do our communication devices or methods signal a label?

The highs and lows of AAC communication

Apart from when I’m at home I never take for granted that I will speak and be easily understood. Of course, in the real world, there are well-informed and well-trained people. These are the people who speak to me directly and make me feel I’m an individual. Unfortunately, there are the too frequent experiences of being ignored or overlooked by others. As a communication aid user one minute I’m on an absolute high. I’ve had a really good 1-1 discussion or small group interaction, or I’ve delivered a well-received presentation or workshop. The next minute I’m gutted that once again people look at me and judge me from outward appearances. I often experience strangers looking to see who I’m with and then speaking to my assistant.

Fear, ignorance or lack of education?

My Mum tells the story about the first time she went to a conference where there were adult augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) users. Before that day the only AAC users she knew were me and a couple of other children. She says she entered the room and was approached by an adult with a communication aid mounted on their power chair. She suddenly found herself unsure about what to do. How should she speak to them? What should she do? Would she get it right? And, this was from someone who lives with an AAC user. New experiences can be scary for us all!

We all like to get things right. However, so often people don’t manage this. Is this behaviour driven by fear, ignorance, or lack of education? The cause appears deep-rooted, the result of ableism in society. The majority of our population is able-bodied. As a consequence, they have probably never thought about what it is like to have a disability. The majority do not use hearing aids, wheelchairs or communication aids, and maybe they know no one who does. Ableism is an attitude or behaviour borne out of the privilege of taking an action for granted. Because you can do something you don’t think about the people who can’t. This results in perpetuating perceptions of difference, stigma and discrimination based on a lack of understanding.

When and where ableism occurs

Recently I was presenting at Naidex, held in the National Exhibition Centre in Birmingham. Entering the concourse from the blue badge parking in my excitement I sped ahead, overtaking another powerchair user. My companions were catching up but I was on my own. The person giving directions took one look at me, looked behind me and clearly made some sort of decision. She chose to speak over my head to the female power wheelchair user I’d overtaken. I was completely ignored. The difference between us? I had a communication aid mounted on my chair, she did not. Was this person’s decision based on the technology mounted on my chair? This is not a comment on Naidex, more the individual who appeared unsure how to interact with me. The actual Naidex team were fantastic.

These types of occurrences happen every day when I’m out and about in the community. I’m frequently spoken over, talked or shouted at, treated as a 3-year-old or patronised. It can happen anywhere and at any time. I assume it is my communication aid that triggers the reaction?

Without realising we all compare ourselves to others. We look at their situation and think they are similar, or different, from us. In terms of connecting with others, we are looking for similarities to ourselves, to be part of the same ‘in-group’. Psychologically we are putting people with a difference in an ‘out-group’. This can be described as a group set apart from ourselves. We really do need to find ways to educate people that difference does not need to be scary.

Ableism and communication impairment

I see on social media lots of disabled people talk about their experiences of being treated differently when out and about. This does appear to be a common issue, whatever someone’s condition. One thing I do find is some other disabled people see my communication aid and sadly some also make assumptions. There is something about having little or no speech that throws people. Maybe this is also a result of societal ableism. In other words, maybe they are forgetting their own privilege of being able to speak. If this makes you think you might want to read my blog on AAC and identity.

My own privileges

We are of course all individuals and having a blanket term of disability as a catch-all isn’t always a helpful descriptor. Coming back to that Twitter post…even with my disability I know I have lots of privileges; I’m white, well educated, a Paralympian and an electronic communication aid user. But I hope that these privileges never let me forget to take the needs and abilities of others into account. We might all be unique and I hope one day we will all be treated equally.

Raising awareness of ableism and communication impairment

It shouldn’t be up to individuals to raise awareness of ableism, including ableism and communication impairment. However, every little we can do helps. Especially when we can speak with children and young people. The key is to catch them at an age where they are forming opinions about what they see in the world around them.

Just for info:

A recent google search suggests:

14 million people will have a communication disability at some point in their lives. That’s 20.8% of the population or more than 1 in 5 people (RCSLT, 2022).

If you found this interesting or

helpful please feel free to share.