We are all different. A big part of my own identity is undoubtedly my physical disability, my communication impairment, and my hearing loss, and all of these contribute to how others see me. Just because I am disabled does not mean I am the same as other disabled people. However, I’ve often felt being a user of AAC and identity are closely linked.

We are all different. A big part of my own identity is undoubtedly my physical disability, my communication impairment, and my hearing loss, and all of these contribute to how others see me. Just because I am disabled does not mean I am the same as other disabled people. However, I’ve often felt being a user of AAC and identity are closely linked.

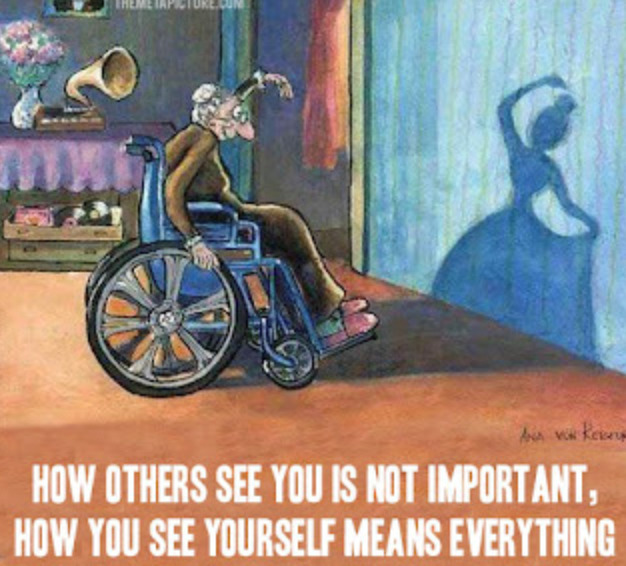

I’ve always loved this visual, and I believe it is true. It is not important how others see us, but it is how we frame ourselves that makes us who we are. Although at times I need a thick skin when it comes to being a user of AAC and identity perceptions.

What is identity?

If you know me then you will know I like to do some reading around subjects when they interest me. Identity is a construct between us as individuals and the rest of the world. In other words, our identity is built on the mix of our own experiences, relationships, and connections. Then, how we think about these, interact with these thoughts, and express them internally to ourselves and outwardly to others.

Identity is a term of contrasts, it is about what we share with others, and the differences we have compared to others. A simple way of showing this is to look at our passports. A passport gives factual information about occupation, nationality, and age, but nothing about our character and our feelings. It is a bland document that only tells basic information. Where we come from, a category we belong to, and how old we are.

Identity is a term of contrasts, it is about what we share with others, and the differences we have compared to others. A simple way of showing this is to look at our passports. A passport gives factual information about occupation, nationality, and age, but nothing about our character and our feelings. It is a bland document that only tells basic information. Where we come from, a category we belong to, and how old we are.

Identifying with some groups, and not others

These categories are sometimes called ‘in and out groups’. The ‘out groups’ are those we don’t identify with. As an individual I self categorise myself as female, I’m not a man. I’m not too keen on football, I’m not able-bodied and I don’t drive a car. But I am many other things and these would form part of my ‘in groups’. These include being female, single, a graduate, a boccia athlete, a lover of music, and good food.

Yet others will see me as completely different, particularly those who don’t know me so well. Words that have been used to describe me are female, then there are labels. These include cerebral palsy, wheelchair user, communication aid user, wears glasses, deaf, with a personal assistant. The common thing here is that I’m female What I think internally about me is not something people can divine without knowing me. The one thing I know is that I have a disability, but I don’t see that it disables me, I lead a full and active life.

Our character, traits, and feelings come from how we imagine ourselves, compared to the view we hold on what we think others see of us. We want others to welcome us into their groups and see us like them. Because of this, we may choose carefully what we wear, maybe how we cut and colour our hair. This may be by wearing our nation’s sports kit or our football team’s scarf. And we might do this by how we speak; our voices identify us by gender, accent, and dialect. As an AAC user this is something I will come back to.

Visual identity

Visual identity

Visuals go a long way to create identity. This photo shows lots of things about me, I’ll let you add the descriptors.

Identity is fluid

Throughout our lives our identity changes. We might have been remainers or leavers during Brexit, now we are all British. I was a full-time student, now I’m a graduate. I’m currently an elite athlete, but at some time in the future I won’t be, because all things move on. Our identity changes with life transitions, who we live with and where we live. So as a social construct it fluctuates through each stage of our lives.

Knowing who we are

Identity is grounded in accepting or knowing who we are. It is about taking our childhood experiences and creating our own story or narrative to fit our experiences. I might have a disability label, but I don’t feel disabled as I have never known anything different. It is about being able to accept or reject our current situation based on not just our childhood experiences, but those that come in adult life. Making sense of the shared values and experiences we had with our parents and family. Understanding the outward values and experiences with the many professions who impacted our lives from health, education, and social care.

Societal views of disability

For me, there was a mix of really positive childhood experiences around AAC and identity from home and primary school. Then that brings us onto the repercussions of how the wider community act towards AAC users. Once out in the big wide world things change. From a policy perspective, you can argue people with CP might be second-class citizens. Unlike other conditions, people with cerebral palsy have no established care pathway and often have to fight for their AAC voice. Once we leave children’s services our care and provision can be left to chance. Early in Covid we heard that people with cerebral palsy, and some other disabilities, were on the do not resuscitate list. Fortunately, that changed, but goodness it says something about government views.

For me, there was a mix of really positive childhood experiences around AAC and identity from home and primary school. Then that brings us onto the repercussions of how the wider community act towards AAC users. Once out in the big wide world things change. From a policy perspective, you can argue people with CP might be second-class citizens. Unlike other conditions, people with cerebral palsy have no established care pathway and often have to fight for their AAC voice. Once we leave children’s services our care and provision can be left to chance. Early in Covid we heard that people with cerebral palsy, and some other disabilities, were on the do not resuscitate list. Fortunately, that changed, but goodness it says something about government views.

A good example, that happens nearly daily, is someone speaking first to my assistant. A judgment has been passed about me being in a chair and surrounded by equipment. Or, the other extreme is someone being kind. They intentionally want to include me but immediately raise their voice, talk slowly and in simple language so I can understand. They may even sign or gesticulate, and as I’m not a signer it doesn’t help communication. I accept this is based on them meaning well but created by a lack of education. When this happens I make it my challenge to nicely change their perceptions. This can only be achieved one person at a time, of first me, and then I hope other disabled people, and especially those who use AAC.

Communication and identity

Everyone’s identity is formed through verbal interactions, and for those of us with speech impairments this presents some obstacles. We all want, and have the right to, express our thoughts, opinions, views and knowledge. We all enjoy sharing our experiences and making up narratives we repeat again and again to tell people things about ourselves. One of my favorite stories is when I was 6 telling my Mum that at school we had done about Queen Elizabeth 1st chopping off heads. Without the appropriate vocabulary and completely out of context imagine the pointing (my Mum is Liz), the actions, and the noises to convey that story. Unsurprisingly this wasn’t successful. That was a pivotal moment for us at home with my communication. And, for me understanding I needed to have access to the right vocabulary on my device. When telling stories it is normal to speak with tone, pace and changing volume to enrich the interaction or the storytelling. Dependent on circumstance we choose specific language, jargon, or words that add meaning to the communicational intent. Then, of course, we add in body language, facial expressions, and gestures to reinforce our message.

Everyone’s identity is formed through verbal interactions, and for those of us with speech impairments this presents some obstacles. We all want, and have the right to, express our thoughts, opinions, views and knowledge. We all enjoy sharing our experiences and making up narratives we repeat again and again to tell people things about ourselves. One of my favorite stories is when I was 6 telling my Mum that at school we had done about Queen Elizabeth 1st chopping off heads. Without the appropriate vocabulary and completely out of context imagine the pointing (my Mum is Liz), the actions, and the noises to convey that story. Unsurprisingly this wasn’t successful. That was a pivotal moment for us at home with my communication. And, for me understanding I needed to have access to the right vocabulary on my device. When telling stories it is normal to speak with tone, pace and changing volume to enrich the interaction or the storytelling. Dependent on circumstance we choose specific language, jargon, or words that add meaning to the communicational intent. Then, of course, we add in body language, facial expressions, and gestures to reinforce our message.

AAC communication and identity

Meredith Allen from Australia, a communication aid user for 50 years, has studied AAC and identity and says that before you can reach an AAC identity you need first to understand there is a disability identity, then that there is the physical element of that identity. This is then coupled with linguistic identity. That is the way in which we speak, so the AAC identity is the electronic voice. The lack until recently of choice of voice means we all sounded the same. The speed of input, pace, and lack of intonation of speech output, and the often restricted access for many to a rich vocabulary all play a part in how we are perceived.

My own identity experience of disability

I’d add to this some of my own experiences from mainstream and special school, and in the wider community. These have led me to believe a hierarchy of disability does exist in our society. First, all disabilities are lumped together as one homogenous group. Surprisingly nearly one in 5 people fall into this disability category. But within this categorization there are many other groups. I’ve found none of them necessarily see themselves as the same or equal to others. Some groups are much closer to the societal norm as able than others. This means they are more easily included in ‘normal’ activities and life, such as someone with a mental health condition or using a blade.

All wearers of glasses do not consider themselves the same. In my experience, a deaf person does not see themselves as the same as someone with a physical disability. Someone who is ambulant does not see themselves as the same as a wheelchair user. A manual wheelchair user does not always see themselves as the same as a power chair user. And, a power chair user who can speak will not easily identify with someone who uses AAC, and who may have a personal assistant always present. Then along comes the perception that an AAC user probably has a learning disability.

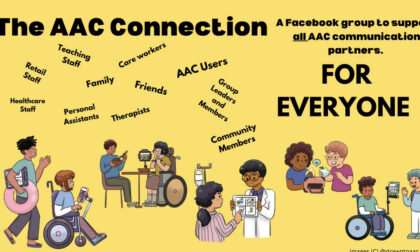

Safety of an AAC community

Friends who use AAC often tell me they are most comfortable within the AAC world, I certainly can agree with this. I first went to the International Society for Augmentative and Alternative Communication (ISAAC) conference at the age of 12, it was a revelation that people wanted to listen to me speak, sought me out, and made me feel valued as an individual. ISAAC and its UK branch, Communication Matters, hold a very special place in my heart. They are places I feel secure and happy to be me, knowing I won’t be judged. That everyone is there with a common interest, AAC.

This brings me back to being accepted for who we are. Within the world of AAC, and with those people who know me well I feel accepted, appreciated, and respected. Within the wider world, I find there can sometimes be a well-meaning but ill-informed conflict between those who put me on a pedestal as being inspirational. Sorry, I’m not! I’m just me. And, the greater number who assume I have a low level of competence or cognition because they see my chair, technology, and assistance before they see me.

What I can say is that I am positive about my AAC and identity. I’m who I am! I wouldn’t want to be anyone else. I’ve grown up with my physical disability, hearing loss and speech impairment (dysarthria). I’ve previously blogged about issues around identity and self-esteem. You can read more here

Very well expressed again Beth. Keep these blogs coming please

Thank you Kim, I’m delighted you are enjoying my blog.